The Pug, with its soulful eyes and deeply wrinkled brow, has long held a place in the hearts of dog lovers. Its visage is one of perpetual concern, a comical and endearing mask that has been celebrated in art, film, and advertising for centuries. This distinct appearance, however, is not a benign quirk of nature but the direct result of intense selective breeding. The very wrinkles that define the breed's charm are, in a cruel twist, a significant source of discomfort and a gateway to a host of serious health problems. The story of the Pug's skin is a powerful case study in how human aesthetic preferences can inadvertently engineer suffering into a living creature.

The origin of these characteristic folds lies in a genetic condition known as dermatological excess. Breeders have, over countless generations, selectively chosen dogs with the most pronounced facial wrinkles to produce offspring that exaggerate this trait. The skin of a Pug produces far more cells than it needs, resulting in heavy, overlapping folds, particularly around the face, head, and neck. While this gives them their unique "puggy" expression, it creates a dark, damp, and poorly ventilated environment between the folds of skin. This microenvironment is a perfect breeding ground for yeast and bacteria, which are naturally present on the skin but are kept in check by exposure to air and light.

Consequently, one of the most common and persistent ailments afflicting the breed is skin fold dermatitis, also known as pyoderma. This is a painful inflammatory infection of the skin within the folds. Owners often first notice a foul, musty odor emanating from their dog, a tell-tale sign of microbial overgrowth. This is followed by redness, itching, and soreness. The dog may rub its face against furniture or scratch incessantly, providing only momentary relief while often exacerbating the inflammation and potentially causing breaks in the skin that lead to secondary infections. Managing this condition is a lifelong commitment, requiring owners to perform daily or weekly cleaning rituals. This involves meticulously separating the folds and wiping them clean with medicated wipes or solutions to remove moisture, food particles, and biological debris. For many Pugs, this is not enough to prevent recurrent flare-ups, necessitating regular courses of antibiotics or antifungal medications, which carry their own risks of side effects and can contribute to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

The problems extend far beyond superficial skin infections. The pursuit of an extremely flat face, a feature intrinsically linked to the wrinkled brow, has led to the condition known as Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS). Pugs have been bred to have shortened skull bones, but the soft tissue inside—the palate, tongue, and throat—has not been correspondingly reduced. This results in a crowded airway, making every breath a struggle. The wrinkles on their nose and face can further obstruct the narrow nasal openings. The effort required simply to breathe normal air is immense, placing constant strain on their cardiovascular system. They snore, snort, and gag loudly even while resting, and are highly susceptible to overheating, as they cannot pant effectively to regulate their body temperature. A short walk on a mildly warm day can become a life-threatening event. The chronic lack of oxygen can lead to sleep apnea and contributes to a state of constant, low-grade stress on their organs.

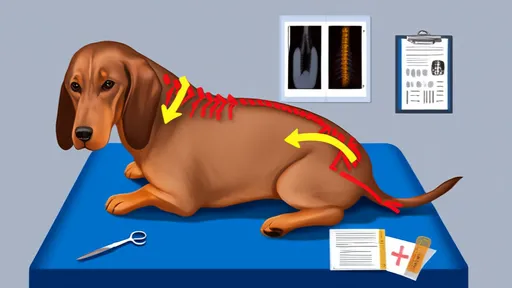

Perhaps the most heartbreaking connection is between the facial structure and ocular health. The extreme folds of skin on a Pug's forehead push downward, and the shallow eye sockets, another feature of the brachycephalic skull, allow the eyes to protrude. This dangerous combination makes the cornea vulnerable to injury from everyday objects like a twig or a sharp corner of a table. More insidiously, the hair from the nasal fold can constantly rub against the surface of the eye, a condition called entropion or trichiasis. This relentless abrasion causes ulcerations, chronic pain, and can lead to scarring or even perforation of the eye, resulting in blindness if not surgically corrected. Many Pugs require multiple surgeries throughout their lives to shorten their palates, widen their nostrils, or remove excess skin folds that threaten their vision and breathing.

The ethical implications of perpetuating this breed standard are profound. Kennel clubs and breed associations worldwide continue to promote an idealized image of the Pug that is synonymous with these extreme features. Show rings often reward the dogs with the deepest wrinkles and flattest faces, sending a clear message to breeders about which traits are valued. This creates a cycle of demand and supply where the health of the animal is a secondary consideration to its conformity to a written standard. Veterinarians and animal welfare organizations have become increasingly vocal, labeling the breeding of such extreme conformations as a form of institutionalized cruelty. They argue that the breed standard itself requires redefinition to prioritize health and function over form, moving towards a "moderate" type with a longer muzzle, less skin excess, and a functional airway.

For the prospective owner smitten by the Pug's charming appearance, the responsibility is significant. Owning one of these dogs is not like owning other, more anatomically typical breeds. It is a commitment to being a full-time nurse. It requires financial preparedness for inevitable veterinary bills, and the emotional fortitude to handle a pet that may never know a day of truly easy breathing. The choice of a breeder is paramount; ethical breeders are those who prioritize health testing and aim for a more moderate, healthier build, even if it means their dogs may not win top prizes in a conformation show. The most ethical choice of all for some may be to decide that loving a breed sometimes means not supporting its continued existence in its current painful form, and to instead opt for a rescue or a different breed altogether.

The deep wrinkles of a Pug are a monument to human desire, etched in living flesh. They represent a history of aesthetic choices that have prioritized a very specific look over fundamental well-being. Each fold tells a story not of natural evolution, but of deliberate design—a design that the dog itself must bear the cost of every single day. As society's understanding of animal welfare evolves, the future of the Pog, and breeds like it, hinges on a difficult but necessary conversation. It is a conversation about whether our appreciation for a certain look justifies the lifetime of medical challenges we have engineered. The challenge is to find a new form of beauty, one defined not by exaggeration, but by health, vitality, and the promise of a life free from preventable suffering.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025